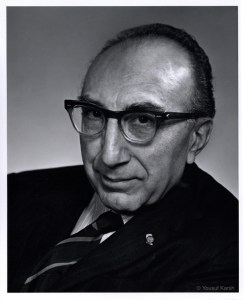

Photo by Yousuf Karsh

By Susan Speaker

In March of 1959, Dr. Michael DeBakey testified in the U.S. House of Representatives about the phenomenal progress made against cardiovascular disease since 1949. Ten years earlier, diseases of the heart and blood vessels consigned millions to lives as invalids, and very often to an early death. These included children born with septal defects (holes in the walls between the heart’s chambers), children and young adults with heart valves damaged by rheumatic fever (caused by streptococcus infection), and older people with blood vessel blockage and aneurysms. Now, DeBakey said, due to increasingly intensive surgical research and “the bold ingenuity and aggressive approach characterizing the surgical attack on these grave diseases,” such cases were no longer hopeless.

DeBakey could speak with authority about progress in treating cardiovascular disease—he was himself one of those bold surgical innovators who carried on extensive laboratory and clinical research. From the late 1940s, he and his colleagues at Baylor University School of Medicine (notably Dr. Denton A. Cooley) were among the surgeons who developed proficiency with one of the earliest cardiac operations: mitral-valve commissurotomy, used to break open tissue scarred by rheumatic fever. However, DeBakey had long been interested in treatments for constricted and blocked blood vessels. A few attempts had been made to surgically treat aneurysms and blockages of the lower-body circulation before 1950, but it was DeBakey who developed and perfected the techniques that truly remedied these conditions. In 1953 he and Denton Cooley did the first American repair of a fusiform aneurysm of the abdominal aorta, removing the compromised section of aorta and replacing it with a preserved aortic section obtained from a cadaver. The following year, they performed a similar resection and graft repair of an aneurysm in the descending thoracic aorta. By 1956, they had done about 800 such operations, working their way up to more difficult repairs of aneurysms of the ascending aorta and aortic arch. Besides developing the surgical technique, DeBakey also developed prosthetic blood vessels made of woven, and later, knitted Dacron during this time, eliminating the need for preserved cadaver material.

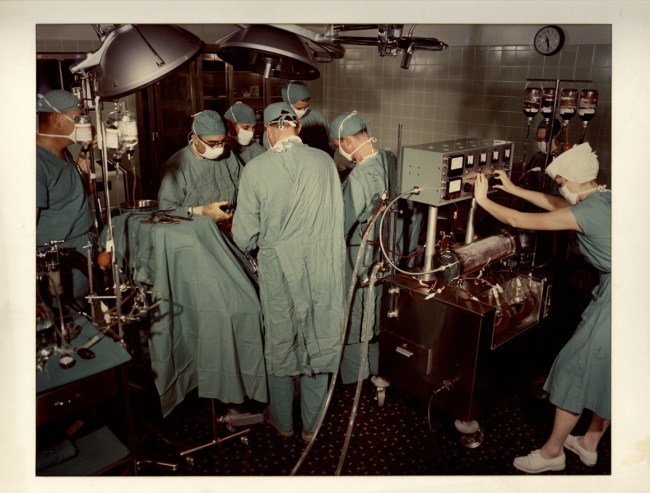

Reproduced with permission of the Baylor College of Medicine Archives

Repairs to the aorta near the heart, and to the heart itself became possible after 1953, when John Gibbon at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia broke through the major barrier to longer cardiac operations, successfully using his heart-lung bypass machine to carry a patient’s circulation for 26 minutes while he repaired a large atrial-septal defect. The early “pump-oxygenators” were often unreliable, and in the first few years, mortality rates for such procedures was quite high, but improved machines were soon developed.

DeBakey, Cooley, and their colleagues quickly adopted the new technology and were among the first to become proficient in open-heart surgery during the 1950s. During 1956, using a modified DeWall-Lillehei bypass machine, they did nearly 100 open-heart surgeries, repairing atrial septal and ventricular septal defects and other congenital heart problems. As he had with vascular surgery, DeBakey rapidly developed better techniques, and advanced the state of cardiac surgery with his careful ongoing analysis of large series of clinical cases.

Courtesy of Katrin DeBakey

DeBakey pioneered several other important surgical techniques during the 1950s. Endarterectomy, in which an artery is opened and cleared of atherosclerotic deposits that are narrowing or blocking the channel, was a technique devised by J. Cid dos Santos in 1947. DeBakey was among the first to use this for blocked arteries in the legs, and in 1953, he did the first endarterectomy on the carotid arteries that supply the brain. Carotid endarterectomy has since become a routine operation for helping to prevent ischemic stroke. His work led him to develop the fundamental concept that many types of vascular disease are segmental; the atherosclerotic plaque that occludes blood vessels (or weakens their walls to cause aneurysm) is localized, rather than distributed all along the artery, and can be effectively treated surgically. Another of his innovations, patch-graft angioplasty, solved a common problem with small-vessel endarterectomy: suturing the artery often constricted its opening. In 1958 he found that grafting a small Dacron patch into the incision prevented such narrowing.

DeBakey would continue to lead the campaign against cardiovascular disease for another forty years, doing some of the first coronary bypass operations and heart transplants, and developing several generations of heart assist devices and artificial hearts, among other accomplishments. He became a renowned surgeon, educator, and medical statesman, and earned many awards and honors. However, it was in that phenomenal decade from 1949 to 1959 that he and other surgical innovators made the quantum leaps that truly established the field of cardiac surgery.

Learn more about Dr. Michael E. DeBakey on NLM’s Profiles in Science site, which features correspondence, published articles, travel diaries, interviews, and photographs from the Michael DeBakey Papers held by the National Library of Medicine. Visitors to Profiles in Science can view photos from DeBakey’s childhood and early career, correspondence with surgical colleagues during World War II, and the journal he kept on a trip to Russia to supervise President Boris Yeltsin’s bypass surgery in 1996. An in-depth historical narrative leads to a wide range of primary source materials that provide a window into Michael DeBakey’s life and major contributions to vascular surgery, medical education, and health care policy. Visitors may also search and browse the collection, and consult a brief chronology of DeBakey’s life, a glossary of terms specific to the collection, and a page of further readings.

The NLM recently received a generous gift from The DeBakey Medical Foundation, to support enhanced access to the Michael E. DeBakey archives and establishment of related programs in the history of medicine. Learn more here.

Susan Speaker, PhD, is Historian for the Digital Manuscripts Program of the History of Medicine Division at the National Library of Medicine.

2 comments