By Susan L. Speaker ~

The National Library of Medicine recently launched a new Profiles in Science site featuring psychiatrist Lawrence Kolb (1881–1972). This Profile presents a curated selection of digitized manuscripts from the Lawrence Kolb Papers together with a narrative “Story” that provides historical context, a chronology of Kolb’s life and career, and a link to further resources to learn even more.

Profiles in Science

Kolb was a career medical officer and administrator in the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) from 1909 to 1945. While he is best known for his pioneering work in drug addiction diagnosis and treatment, his long PHS career included an impressive range of other duties. Kolb served as a quarantine officer on the Delaware River and a medical inspector at the Ellis Island immigration station, where he helped develop tools and protocols for immigrant intelligence testing. And he organized and served as director for three new PHS hospitals (one for shell shocked WWI veterans, one for chronically ill federal prisoners, and one for drug addicts) before his final assignment as Assistant Surgeon General in charge of the PHS Division of Mental Hygiene. The Lawrence Kolb Profiles site includes correspondence, reports, publications, and speeches that chronicle Kolb’s many activities and accomplishments. At the same time, they provide a window to the experiences of Public Health Service officers during the first half of the twentieth century, which was an era of rapid growth and transformation in medicine, public health, and psychiatry, within the larger context of massive immigration and other social changes, two world wars, and the Great Depression.

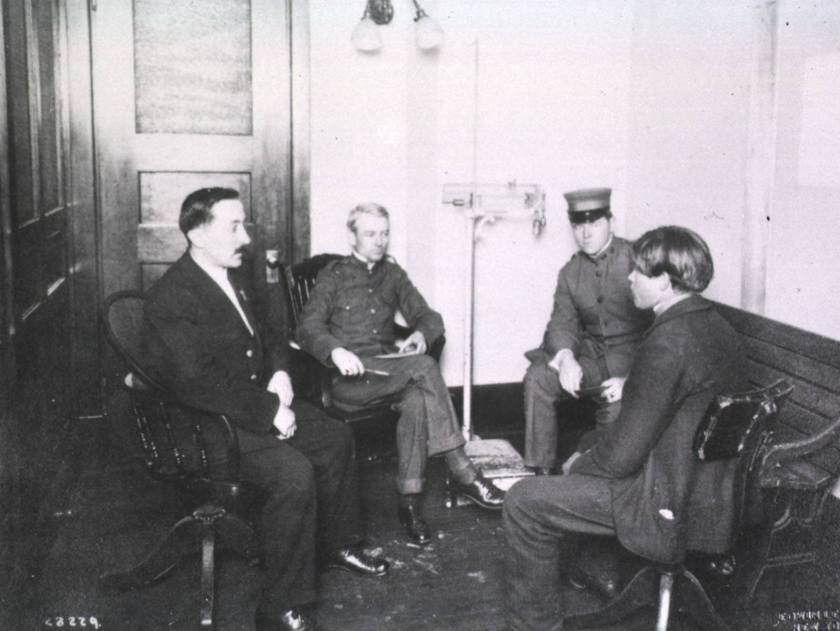

Kolb received his MD from the University of Maryland in 1908, and joined the PHS the following year. In his first duty station, he boarded and inspected ships, passengers, and cargo travelling up the Delaware River, quarantining any that carried contagious diseases. As an immigration inspection officer at Ellis Island from 1913 to 1919, Kolb was part of a group that developed and evaluated intelligence tests (a new assessment method at the time) for screening prospective immigrants. A decade later, he would again work with intelligence testing while posted overseas in Dublin, Ireland. Kolb’s papers show how this process was complicated not only by cultural and language differences, but by American attitudes and assumptions about foreigners, and about people with intellectual disabilities.

Profiles in Science

In his first administrative post, Kolb was in charge of Public Health Hospital #37 in Waukesha, Wisconsin, established to treat WWI veterans suffering from neuropsychiatric disorders, particularly “shell shock.” Shell shock or “war neurosis,” (which would now be called a type of post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD) emerged as a new illness during the war. Its various manifestations posed diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for psychiatrists and other physicians trying to determine why it affected some soldiers and not others, and whether it was a truly disabling condition or just a form of malingering. The Kolb Papers include correspondence regarding several patient complaints that the medical staff didn’t consider their PTSD legitimate, and neglected them.

Public concern about opiate addiction grew after WWI, as it became increasingly associated with recreational drug use and with criminal activity (partly because of aggressive enforcement of the 1914 Harrison Narcotics Act). In 1923, hoping to better understand the scope and psychosocial causes of illicit drug use (which might help in prevention and treatment efforts) the Surgeon General assigned Kolb to study the problem. Kolb’s five-year investigation yielded much new information, including the best estimate of addict numbers to date. His most important achievement was a diagnostic framework for addiction that described five different “psychopathological” types of addicts, based on his analysis of several hundred drug users’ habits, social situation, education, medical history, and other factors. Kolb’s framework was rapidly adopted by psychiatrists and became the standard for the next 30–40 years. Although the federal government would take a predominantly law enforcement approach to addiction from the 1920s, Kolb adamantly defined drug use as a medical disorder requiring treatment rather than a crime requiring punishment.

Profiles in Science

From 1932 to 1934, Kolb served as superintendent at another new federal facility, the Medical Center for Federal Prisoners, in Springfield, MO, which was to be, Kolb stated, “a departure from existing methods in the treatment of criminals.” This hospital cared for chronically ill or disabled prisoners, including many with mental illnesses, who couldn’t be adequately treated in regular prison infirmaries. Besides providing more humane care, the PHS physicians, acknowledging connections between mental illness and crime, hoped to study and learn from their prisoner patients.

Because of his expertise on addiction, Kolb was assigned in 1934 to head the first federal narcotics hospital—a huge hybrid institution that provided treatment and rehabilitation for federal convicts who were also addicts, along with addicts who entered voluntarily. Like the Springfield medical center, the narcotics “farm” approached and treated patients’ criminal behavior as rooted in psychiatric illness and social maladjustment, rather than moral depravity. This reflected gradually changing public and professional perceptions of mental illness in America.

Profiles in Science

As Assistant Surgeon General in charge of the PHS Division of Mental Hygiene (1938–1945), Kolb expanded mental health services and training to government personnel and in 1939 drafted a bill for a national neuropsychiatric institute to carry out mental health research within the PHS. Though not implemented immediately, his proposal was taken up after WWII and served as a template for the National Institute of Mental Health at the National Institutes of Health, established in 1949. After leaving the PHS in 1945, Kolb applied his mental health expertise to state-level administrative reforms in California and Pennsylvania for several years. He also remained a staunch advocate of a medical approach to addiction, and a critic of harsh drug laws.

Courtesy Kay Harris of Medical Press, Inc.

Profiles in Science

We invite you to explore Dr. Kolb’s remarkable career and work through the documents and resources provided on the new Lawrence Kolb Profiles in Science site.

Profiles in Science presents the lives and work of innovators in science, medicine, and public health through in-depth research, curation, and digitization of archival collection materials. National Library of Medicine (NLM) historians and archivists review, study, and select documents from the NLM’s Archives and Modern Manuscript collections and collaborating institutions to bring the public biographical stories and direct access to supporting primary sources.

Susan Speaker, PhD, is Historian for the Digital Manuscripts Program of the History of Medicine Division at the National Library of Medicine.

I come across this article during my search and found really helpful

That’s great that the article was helpful. Thanks for your comment and good luck with your research!

“Although the federal government would take a predominantly law enforcement approach to addiction from the 1920s, Kolb adamantly defined drug use as a medical disorder requiring treatment rather than a crime requiring punishment.”

So, criminalization regarding drug use/abuse (The War on Drugs) is not simply a point of view embraced only in recent times by those who may not think highly of perhaps more humanistic methods of addressing the issue. It seems that humanistic thought becomes relegated to a kind of “soft on crime” category by some law and order advocates. What will it take, in your opinion, for more enlightened rather than reactionary thought to get transferred into federal and state policy?

Thank you for your thoughtful comment. NIDA is the lead federal agency supporting scientific research on drug use and addiction and an excellent resource for questions related to addiction.